No Avoiding Time: an essay on Inherent Vice

We open on a lost paradise. Taking a cue from the ‘68-er parole “Under the paving-stones, the beach!” - which opens Pynchon’s book and that arrives in the film at the very end, after the credits - the first shot of Inherent Vice suggest an alternate vision: “Between the houses, the ocean…”

A few melancholy dot dot dots are here more appropriate than the hopeful ‘68-er exclamation mark, as it's no longer a question of a revolutionary tearing-up-of-streets to get to the essence of things underneath, but rather of succumbing to looking at where the beach already is, and dreaming. The film presents a world where power lies in the tentacles of shadowy entities driven by money and conformism, and our hippie hero Doc Sportello, private investigator, is longing for the very recent past where this seemed like it could have been different. In the 1973 of the film, the possibility of utopia has been supplanted by paranoia and nostalgia, and the waters of these beaches rather stand for the relentless flowing-on of time, of constant flux, that fluxed right by hope and into something very sinister.

The film shows us a universe tending towards disorder. As it tells us: eggs break, chocolate melts. Girlfriends become “ex-old- ladies”. Experience lost to the past, continuously, and chaos building gradually. It's this chaos that gets us closest to our man Doc.

The process of watching the film is one of constantly having to realign yourself to a barrage of new, chaotic information, with little signaling as to what’s actually significant - everything carrying the same feeling of cosmic importance. An overwhelming barrage of newness all the time, and Doc just wants his ex-old lady. Nostalgia as a drug to dampen the frustrations of constant change. The hope of reclaiming a little bit of that past, through his former girlfriend Shasta Fay, drives him on, but the further he goes into the world, foggier it gets, and the mystery deepens rather than untangles.

These continuous push-ins on people’s faces as they tell their intricate stories just highlight the loss of the moments immediately before. Can you keep the plot in your head? You just heard it. It slips away.

Does it ever end? Of course it does. It did.

Unavoidably.

That said, the essentials of the plot aren’t really that complicated, and much of it is even spelled out directly in the film, it’s more the presentation that makes it dense. In essence most of the mysteries in the film are tied to how the Chinese heroin cartel The Golden Fang not only traffic drugs, but also control the people selling them and the institutions addicts are sent to kick their habits and to fix their destroyed teeth.

It was occuring to Doc now, something Jade said once about vertical integration, that if the Golden Fang can get its customers strung out, why not turn around and sell them a program to help kick? Get them coming and going. Twice as much revenue. As long as American life was something to be escaped from the cartel could always be sure of a bottomless pool of new customers.

In addition to this you have the predatory real-estate dealings of Mickey Wolfmann, who after an LSD-induced guilt-trip turns utopian socialist, which results in the FBI placing him in one of the institutions mentioned above to "reform" him, and the story of Coy Harlingen, saxophonist turned informer, who's been embedded into a neo-nazi group that traffics heroin for The Golden Fang, and now cannot get out. All these strands are intertwined, and the additional smaller mysteries, along with a generally chaotic way of presenting the information, makes it all pretty foggy. Still, this is essentially what's needed to get to the core emotions of the film. The plot mechanics are much more chaotic than my outline, and I'm still unsure about many details in the film, but nesting out all the threads won't bring anyone any closer to what the film is about.

It's not that the mystery is unimportant, but the way it’s handled is where the real point is. The film presents the world as a foggy chaos of information, where a vague conspiracy seems to be tying things together. The central feeling of the film is a feeling of powerlessness around these shadowy foggy forces that make things happen in the world. A big and brutal machinery of power...but where? We just see its tentacles and avatars, and can only imagine a gigantic creature in the fog somewhere, as when Doc (but not we) catches a glimpse of boat The Golden Fang only goes “I don’t know what I just saw…”, as if it was something out of Lovecraft.

There’s a mythologizing mode going through a lot of the film. The voice-over of the Sortilége character delivers most of it, but they generally have the feel of vocalizing Doc’s thoughts. We constantly see Doc's eyes darting around, scanning the environment, but they are just as much scanning inwards, attempting to tie everything together in his mind, in a grand vision of where he feels the world is heading.

His thoughts describe big historical movements and give us a feeling that the plowing onwards of moneyed power, of the penthouses erected over social housing, the idealist and utopian drug culture of the late sixties being supplanted by heroin culture and “anti-subversion” institutions, of hippie cultures infiltrated by white supremacists, are more than accidents, but something that seems hardwired into the fabric of the universe. Time levels out everything, and only the powerful can work against it. And the powerless? And those like Doc that don’t want power? There’s a melancholic and deterministic feeling in the film that the powerless will always be plowed over, and that an idealistic person in power (like Wolfmann) will always be put in his place again. In this way the film, or perhaps just Doc, is deeply pessimistic, though it does celebrate small, local victories within this fabric.

The indifferent grind of time, grinding past all the things you are attached to, results in more myths: nostalgic ones. Nostalgia feeds off the lacks left behind by time, and creates visions of past golden ages. For Doc: the brief years of the hippie dream and his time with Shasta. The colors of the film reflects this feeling of a time slowly passing. They are mostly toned down, but in between we get moments where they are highly saturated, as if water has been spilled over a bonfire without killing all the flames.

All we see of Shasta and Doc’s former relationship is filtered through his rosy fantasies, so we never quite know what it was like, but it's clear that those fantasies have little to do with their relationship as it is now. The happiness of the flashbacks are now exchanged with power plays and pettiness. A myth completely deflated by reality. Doc only really longs for Shasta when they’re apart. When they’re together mundanity sets in. This deflation of the mythic mode happens several times in the film, as in this passage from Sortilége/Doc:

Was it possible that at every gathering, concert, peace rally, love-in, be-in and freak-in, here, up North, back East, wherever - some dark crews had been busy all along, reclaiming the music, the resistance to power, the sexual desire from epic to everyday, all they could seep up, for the ancient forces of greed and fear. “Gee,” he thought, “I don’t know”.

The thoughts just become too big for Doc. His grand, mythic vision just on the verge of being articulated, but proving too big and chaotic to be contained. Too many threads to pull together, and the thought falls apart.

I already mentioned the scene where Doc, but not we, catches a glimpse of The Golden Fang (the boat) in the fog, that builds up a feeling of the boat as something indescribable, unknowable. But this scene is followed up in a curious way: we cut to daytime and we simply get to see the ship, in all its mundanity. The myth completely deflated again. Not that the mystery surrounding it is gone, far from it, but it carries none of the cosmic feelings of the previous scene.

It’s a film where the grand but simplified abstractions of myth and mind constantly seems to stumble and fall into slapstick and a worldly, bodily chaos. We simply can't contain the world in our heads, so it will always surprise us. Physical beings struggling to meet a chaotic world. Our little man Doc stumbling on. A botched jump, a door cartoonishly kicked down, a whack to the head and a Looney Tunes-tumble. Or in its less comedic mode: a whack whack whack to the head until dead.

Inherent Vice presents a host of characters whose faces and bodies burst forth with unpredictability. Faces go in the strangest directions. The performances lean heavily on surprising and unusual expressions. They all have that “heavy combination of face ingredients” that Sortilége describes. Their faces twitch and turn, many of the characters seeming on the brink of insanity, struggling to keep up a personality in the face of increasing chaos.

This is of course by now a classic PTA trope: The tightly organized personality that hides torrents of emotion just under the surface of their faces. The characters in Inherent Vice are less histrionic than usual, but this just means they're struggling all the more to keep their emotions in. Rather than the usual bursts of emotions, everyone in Inherent Vice seem rather to bubble.

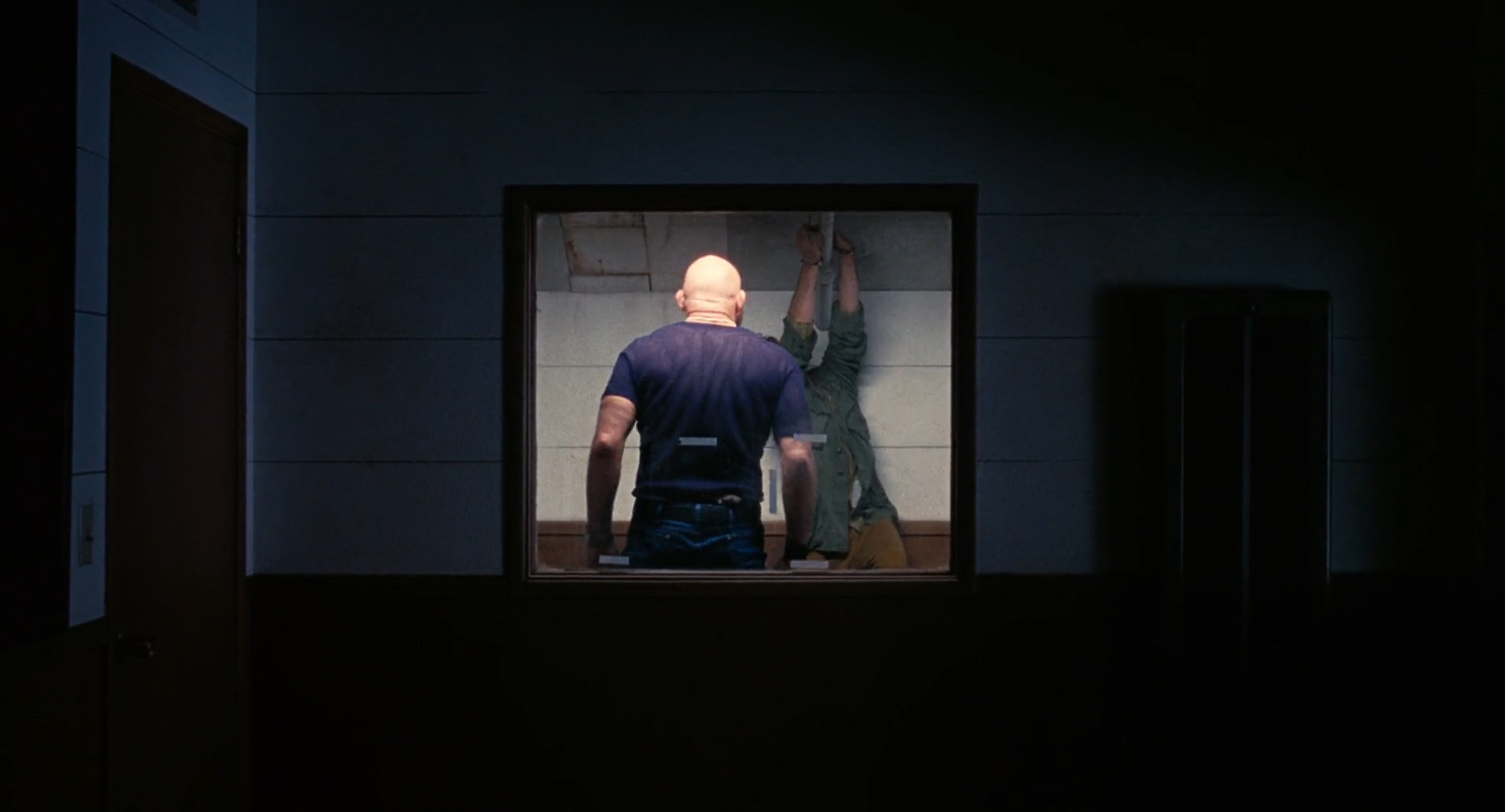

And what a pressure-cooker character Bigfoot is. His inner chaos is so great that he has to hold it in by becoming a literal square. No straight lines in nature but Bigfoot’s hair sure is close.

Bigfoot is probably the character who most fits the classic PTA-mould. Like Frank T.J. Mackey, Daniel Plainview and Lancaster Dodd, Bigfoot’s personality is a tightly organized structure that tries and fails miserably to hide chaos (or, maybe rather: it needs to be so tightly organized because the oppositional forces are so powerful). The clearest hint we get of the repressed chaos inside him doesn't come through his constant outbursts, but through the way he unconsciously mourns his murdered partner through practically fellating frozen bananas.

In a film about power and powerlessness, Bigfoot embodies an in-between feeling - a longing for more power than he actually has. He’s a cop who wants to be an actor, and frustrated with his lack of respect and power in either field. The frustrations boil out of him in every frame, probably pushing him further and further away from the respect he craves.

The most powerful character we meet in the film is Crocker Fenway, though he too is only an avatar of The Golden Fang (he is one of their lawyers). The clearest marker of his power might be the stillness of his face - a pretty shocking stillness in this film. As if his chaos has been locked so far behind his eyes that showing any emotion other than a constant, stern disdain is no longer possible. But even he, when he talks about his daughter, shows signs of chaos. The way he can only describe his ideas of what might have gone on between his daughter and Dr. Blatnoyd through descriptions of the tacky decór of their hotel rooms seem to hint at much more extreme fantasies being repressed, like Bigfoot and his banana.

The descriptions of the decór tie into another aspect of PTA’s films that is perhaps clearer in this film than it’s ever been: the relationship between power and architecture. It’s always been a part of the fabric of his films, but Inherent Vice gives us the first real thematization of this through Mickey Wolfmann’s story.

The strong contrasts in power we often find in PTA’s films have naturally manifested themselves in the kind of buildings we see portrayed, that are often (and more and more these last few films) either opulent semi-castles or extremely stripped down, with bare white walls. It's not always so clear cut of course, but a great deal of the spaces of the film fall into this dichotomy.

The Wolfmann-plot makes the contrasts between the in-between non-places and opulent semi-castles all the more loaded in Inherent Vice. The film’s thematizing of the grind of power - social housing bulldozed for mansions - makes it seem like every in-between place is a potential target for bulldozing. Only the mansions and institutions feel massive and powerful enough to be safe.

Opulent, powerful spaces

Stripped down, vulnerable spaces

The institutional buildings get head-on establishing shots that highlight their size and clear lines (in stark contrast to the overall chaos in the film). These wide shots are of course nothing special, and rather a cliché in most films, but there are very few of them in all of PTA's films, and in a film that is explicitly about power they are worth mentioning. The tooth-shaped Golden Fang building even gets a classic, ominous upwards tilt, along with Doc’s view, to accentuate his smallness and its power.

And Doc, he must inevitably pay rent to some other Fenway. Our man Doc has very little power, and refuses the possibility of getting more of it at the end when Fenway offers him money. He achieves few things by design, and the reason he even lives at the end is due to the serendipity of having returned Fenway’s daughter to him one time long before the events of the film even started. Nevertheless, this act also facilitates his real victory in the film: returning Coy to this family.

It's the happiest moment in the film, but in the end, despite this victory, the injustices of gentrification and the vertical integration of The Golden Fang are left running. Making things happen in the world, plowing against entropy, is easier for the large than for the small, and Doc is left with the possibility of doing a small good deed, now that the grander wave of idealism seems to have died out. We leave Doc still dreaming of the very recent past, when power and change seemed to be in the hands of people who longed for something better:

There’s no avoiding time. The sea of time. The sea of memory and forgetfulness. The years of promise gone and unrecoverable. Of the land almost allowed to claim its better destiny, only to have that claim jumped by evildoers known all too well, and taken instead, and held hostage to the future we must live in now, forever.

In the end he’s “back” with Shasta, seemingly where he wanted to be, living in “the past”. Except of course it isn’t. The newness, strangeness, of the situation just seems to bring home the fact that this isn’t the past at all. This doesn’t mean we’re back together. It’s still something new, and always will be. Something’s off, and you can see it in Doc’s eyes. What’s wrong here? The myth of Shasta deflated, along with hope of the utopian past ever returning. So now what? Where to? Everything outside the car is fog.

Shasta’s there, anyway, right now. In the moment. And their common joking, though in a decidedly minor key, show some connection.

It's a little bright thing to cling to in the chaos.

But in the end, of course, eventually:

Any day now I will hear you say "Goodbye, my love"

And you'll be on your way

Then my wild beautiful bird, you will have flown, oh

Any day now I'll be all alone, whoa